Osho - Pahalgam is one of the most beautiful places in the world. That

is where Jesus died, and he died at the age of one hundred and twelve.

But he got so fed up with his own people that he simply spread the story

that he had died on the cross.

Of course he was crucified -- but you have to understand that the Jewish

way of crucifixion was not the American way. It was not sitting in a

chair, and with just a push of a button you were no more; not even time

to say, "God forgive these people who are pushing the button, they don't

know what they are doing." They know what they are doing! They are

pushing the button! And you don't know what they are doing!

Jesus would not have had any time if he had been crucified in the

scientific way. No, it is a very crude way that the Jews followed.

Naturally, it sometimes even took twenty-four hours or more to die.

There have been cases of people having survived for three days on the

cross, the Jewish cross I mean, because they simply nailed the man by

his hands and his feet.

The blood has the capacity to clot; it flows for a while, then it clots.

The man is, of course, in immense pain, in fact he prays to God, "Please

let it be finished." Perhaps that is what Jesus was saying when he said,

"They don't know what they are doing. Why have you forsaken me?" But the

pain must have been too much, for he finally said, "Let thy will be

done."

I don't think that he died on the cross. No, I should not say that "I

don't think..." I know that he didn't die on the cross. He had said,

"Let thy will be done"; that's his freedom. He could say anything he

wanted to say. In fact, the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate, had fallen

in love with the man. Who would not? It is irresistible if you have

eyes.

But Jesus' own people were busy counting money; they had no time to look

into the eyes of this man who had no money at all. Pontius Pilate for

one moment had even thought to release Jesus. It was in his power to

order his release, but he was afraid of the crowd. Pilate said, "It is

better that I should keep out of their business. He is a Jew, they are

Jews -- let them decide for themselves. But if they cannot decide in his

favor then I will find a way."

And he found a way, politicians always do. Their ways are always

roundabout; they never go directly. If they want to go to A, they first

go to B; that's how politics works. And it really works. Only once in a

while it does not work. I mean, only when there is a non-political man,

then it does not work. In Jesus' case also, Pontius Pilate managed

perfectly well without getting involved.

Jesus was crucified on the afternoon of Friday, hence "Good Friday."

Strange world! Such a good man is crucified, and you call it "Good

Friday." But there was a reason, because Jews have... I think Devageet,

you can help me again -- not with a sneeze, of course! Is Saturday their

religious day?

"Yes, Osho."

"Yes, Osho."

Right... because on Saturday nothing is done. Saturday is a holiday for

the Jews; all action has to be stopped. That's why the Friday was

chosen... and late afternoon, so by the time the sun sets the body has

to be brought down, because to keep it hanging on Saturday would be

"action." That's how politics functions, not religion. During that

night, a rich follower of Jesus removed the body from the cave. Of

course, then comes Sunday, a holiday for everybody. By the time Monday

comes, Jesus is very far away.

Israel is a small country; you can cross it on foot in twenty-four hours

very easily. Jesus escaped, and there was no better place than the

Himalayas. Pahalgam is just a small village, just a few cottages. He

must have chosen it for its beauty. Jesus chose a place which I would

have loved myself.

I tried continuously for twenty years to get into Kashmir. But Kashmir

has a strange law: only Kashmiris can live there, not even other

Indians. That is strange. But I know ninety percent of Kashmiris are

Mohammedan and they are afraid that once Indians are allowed to live

there, then Hindus would soon become the majority, because it is part of

India. So now it is a game of votes just to prevent the Hindus.

I am not a Hindu, but bureaucrats everywhere are delinquents. They

really need to be in mental hospitals. They would not allow me to live

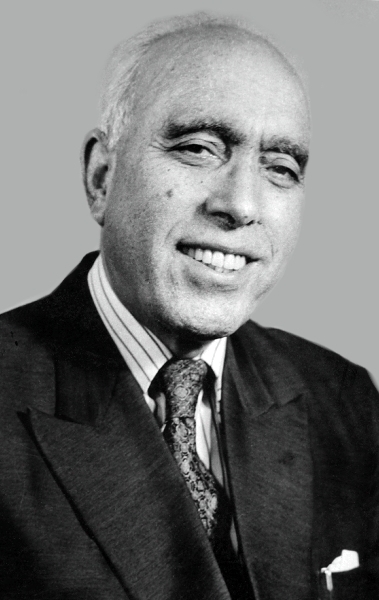

there. I even met the chief minister of Kashmir, who was known before as

the prime minister of Kashmir.

It was such a great struggle to bring him down from prime ministership

to chief ministership. And naturally, in one country how could there be

two prime ministers? But he was a very reluctant man, this Sheikh

Abdullah. He had to be imprisoned for years. Meanwhile the whole

constitution of Kashmir was changed, but that strange clause remained in

it. Perhaps all the committee members were Mohammedans and none of them

wanted anybody else to enter Kashmir.

I tried hard, but there was no way. You cannot enter into the thick

skulls of politicians.

I said to the sheikh, "Are you mad? I am not a Hindu; you need not be

afraid of me. And my people come from all over the world -- they will

not influence your politics in any way, for or against."

He said, "One has to be cautious."

I said, "Okay, be cautious and lose me and my people."

I said, "Okay, be cautious and lose me and my people."

Poor Kashmir could have gained so much, but politicians are born deaf.

He listened, or at least pretended to, but he did not hear.

I said to him, "You know that I have known you for many years, and I

love Kashmir."

He said, "I know you, that's why I am even more afraid. You are not a politician, you belong to a totally different category. We always distrust such people as you." He used this word, distrust -- and I was talking to you about trust.

At this moment I cannot forget Masto. It was he who introduced me to Sheikh Abdullah, a very long time before. Later on, when I wanted to enter Kashmir, particularly Pahalgam, I reminded the sheikh of this introduction.

He said, "I know you, that's why I am even more afraid. You are not a politician, you belong to a totally different category. We always distrust such people as you." He used this word, distrust -- and I was talking to you about trust.

At this moment I cannot forget Masto. It was he who introduced me to Sheikh Abdullah, a very long time before. Later on, when I wanted to enter Kashmir, particularly Pahalgam, I reminded the sheikh of this introduction.

The sheikh said, "I remember that this man was also dangerous, and you

are even more so. In fact it is because you were introduced to me by

Masta Baba that I cannot allow you to become a permanent resident in

this valley."

Masto introduced me to many people. He thought perhaps I might need

them; and I certainly did need them -- not for myself but for my work.

But except for very few people, the majority turned out to be very

cowardly. They all said, "We know you are enlightened...."

I said, "Stop, then and there. That word, from your mouth, immediately

becomes unenlightened. Either you do what I say, or simply say no, but

don't talk any nonsense to me."

They were very polite. They remembered Masta Baba, and a few of them

even remembered Pagal Baba, but they were not ready to do anything at

all for me. I am talking about the majority. Yes, a few were helpful,

perhaps one percent of the hundreds of people that Masto introduced me

to. Poor Masto -- his desire was that I should never be in any

difficulty or need, and that I could always depend on the people he had

introduced me to.

I said to him, "Masto, you are trying your best, and I am even doing

better than that by keeping quiet when you introduce me to these fools.

If you were not there I would have caused real trouble. That man for

instance, would never have forgotten me. I control myself just because

of you, although I don't believe in control, but I do it just for your

sake."

Masto laughed and said, "I know. When I look at you as I am introducing

you to a bigwig, I laugh inside myself thinking, `My God, how much

effort you must be making not to hit that idiot.'"

Sheikh Abdullah took so much effort, and yet he said to me, "I would

have even allowed you to live in Kashmir if you had not been introduced

to me by Masta Baba."

I asked the sheikh, "Why?... when you appeared to be such an admirer."

He said, "We are no one's admirer, we admire only ourselves, but because he had a following -- particularly among rich people in Kashmir -- I had to admire him. I used to receive him at the airport, and give him a send-off, put all my work aside and just run after him. But that man was dangerous. And if he introduced you to me, then you cannot live in Kashmir, at least while I am in power. Yes, you can come and go, but only as a visitor."

He said, "We are no one's admirer, we admire only ourselves, but because he had a following -- particularly among rich people in Kashmir -- I had to admire him. I used to receive him at the airport, and give him a send-off, put all my work aside and just run after him. But that man was dangerous. And if he introduced you to me, then you cannot live in Kashmir, at least while I am in power. Yes, you can come and go, but only as a visitor."

It is good that Jesus entered Kashmir before Sheikh Abdullah. He did

well by coming two thousand years before. He must have been really

afraid of Sheikh Abdullah. Jesus' grave is still there, preserved by the

descendants of those who had followed him from Israel. Of course men

like me cannot go alone, you can understand. A few people must have

followed him there. Even though he went far away from Israel, they must

have gone with him.

In fact the Kashmiris are the lost tribe of Hebrews of which the Jews

and Christians both talk so much. The Kashmiris are not Hindu, nor of

Indian origin. They are Jewish. You can see by looking at Indira

Gandhi's nose; she is a Kashmiri.

She is imposing emergency rule in India -- not in name but in fact.

Hundreds of political leaders are behind bars. I had been telling her

from the very beginning that those people should not be in parliament or

assemblies or in the legislature.

There are many kinds of idiots, but politicians are the worst, because

they also have power. Journalists are number two. In fact they are even

worse than politicians, but because they have no power, they can only

write, and who cares what they write? Without power in your hands then

you may have as much idiocy as possible, it cannot do anything.

Source

- Osho Book "Glimpses of a Golden Childhood"